What happens when we deprive our lives of play activities? Research suggests there must be importance in making time for play. Despite the risk of not being on high alert for predators, or taking this time to look for food, animals still put a priority on this type of activity. At the Canadian Centre for Behavioural Neuroscience, PhD candidate Rachel Stark is working with Dr. Sergio Pellis and Dr. Robbin Gibb to find the precise mechanisms that play influences for social and brain development.

"We have pieces to this puzzle but not a direct connection," says Rachel. She started her academic career hoping to study the autism spectrum disorder, but her very first project with rats and the ability to see changes in their brains at the micrometer level broadened her aspirations. "I have always found the idea of nature and nurture to be fascinating, and that experiences that you have during development can have lasting impacts on the brain, and subsequently behaviour."

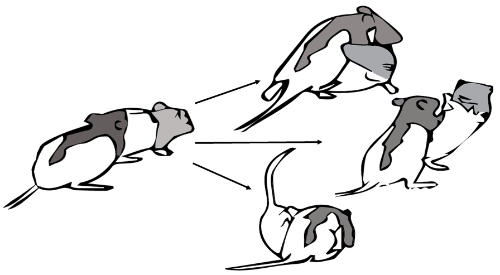

To explore this in juvenile development, Rachel is pioneering a method called the Stranger Paradigm to compare the differences between play and non-play brains. She is rearing two groups of rats into early adulthood: rats that grow up with lots of play experiences, and rats that do not. To test the social skills of these rats, she puts a play-experienced rat and a play-inexperienced rat in neutral territory to see what they do.

"When unfamiliar adult male rats meet in a neutral territory they play to assess and assert their dominance." The inexperienced group of rats are unable to navigate this social interaction and escalate the encounters by biting the rump of the other. "Now, to my knowledge, there are no rats that are trained medical doctors, so being bitten is bad, they could get an infection and die. Therefore, being able to navigate these situations without injury is important, and play seems to be important in giving rats the social skills to do so."

Previous research has shown that rats with limited play experiences have an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex oversees executive functions you use every day like decision making, impulse control, and short-term memory. Having rich play experiences during childhood fine-tunes these executive functions, leading to improved social competence.

But why rats?

By studying rats, she can conduct the research necessary to pinpoint what aspects of play are the most crucial for the development of adult social skills. Dr. Andrew Iwaniuk's lab has specialized software that allows Rachel to create a 3D rendering of tissue and neurons to see the differences between play-experienced and play-inexperienced rats up close. Sharing these discoveries with researchers studying humans will help them develop informed interventions for neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, ADHD, or depression.

Fascinated? Want to learn more? Rachel's supervisor Dr. Robbin Gibb is giving an online community lecture on play and brain development on Thursday, February 18 at 7:00 p.m.!