Pictured above is a canola field in Taber, AB, where Dr. Romero gathered soil samples for his current project.

This week we're chatting with Dr. Carlos Romero, a postdoctoral fellow doing excellent work in unraveling the complex systems of soil, crops, and land resilience to help people like farmers and policy makers make sense of it all.

If you like this, don't miss the next Agri-Food Summer Speaker Series talk on Modern Crop Production! Register to attend this online event (it's free!) on July 27th.

Hi Carlos! Pleasure to chat with you today about your work. You’ve been a postdoctoral research fellow here at uLethbridge for the last couple of years – where has your research been taking you?

My current research is centered on conservation agriculture and its impact on soil organic carbon sequestration in southern Alberta. Croplands are labeled as "climate change mitigators" given their ability to trap atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), a well-known greenhouse gas, as humus or soil organic matter (OM). Soil OM is a complex mixture of compounds, mainly carbon, derived from plant litter decomposition. Nowadays, its accumulation in the soil is receiving considerable interest from farmers, policymakers, and industry stakeholders. Why? Because soil OM represents a significant reservoir of stable carbon and a valuable pool of nutrients for plant growth.

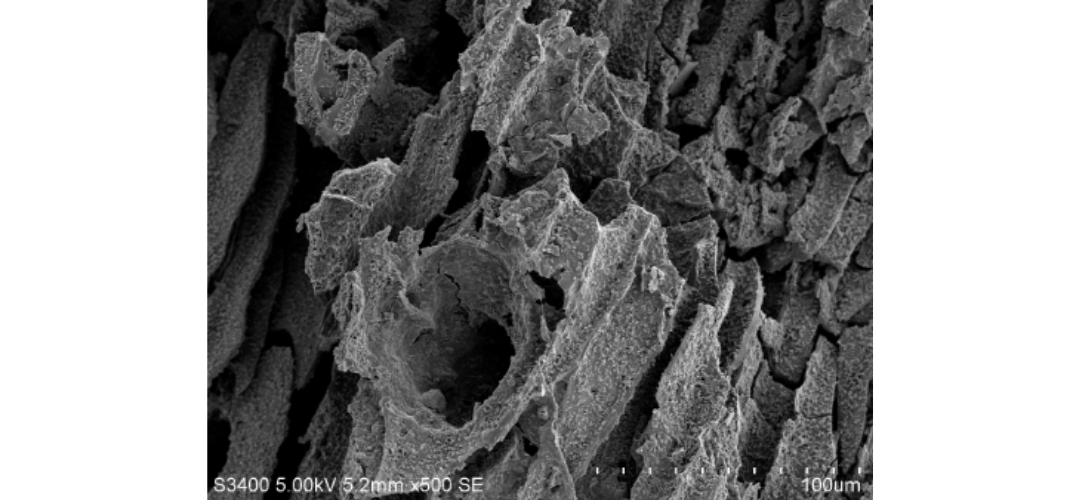

Increasing awareness of this process has opened a tremendous opportunity in the farming industry. For example, healthy soils are now part of "verified carbon markets," which are corporate programs in which enrolled farmers receive money for keeping soil OM in the ground, given that fields are managed adequately for enough time. With the support of my supervisor, Dr. Paul Hazendonk, I partnered with the Food Water Wellness Foundation, a non-profit located in Olds, AB, to successfully launch a soil organic carbon characterization effort in southern Alberta via a Mitacs Accelerate research grant. We aim to fill the gap of current soil carbon initiatives by providing qualitative information on the types of soil OM being accumulated or lost due to agricultural practices in western Canada. Being a diverse pool of organic carbon, not all soil OM is created equal and may behave differently in the environment depending on its properties. With Paul, we are now probing the carbon chemistry of soil profiles up to 1 m of depth utilizing a state-of-the-art technique called 13C nuclear magnetic resonance at the University of Lethbridge NMR Facility.

My previous work at the University of Lethbridge was also focused on carbon, specifically biochar (a charcoal-like substance). Supervised by Dr. Erasmus Okine, I was part of a multi-disciplinary cohort of scientists that investigated the inclusion of biochar in cattle feed as a tool to mitigate enteric methane (CH4) production (aka, methane produced from livestock digesting their food). I lead several laboratory-, greenhouse- and field-based experiments targeting new approaches to incorporate the use of biochar in Canadian agriculture, considering both direct and indirect CH4 sources, including ruminal fermentation (meaning fermentation that happens in the large first compartment of the stomach), manure, compost, and soil. Our project was the first one in North America that provided a holistic perspective to the emerging use of biochar in animal feeding, exploring its potential as a carbon-rich amendment to improve animal husbandry along the cascading way.

It feels as though you are working with a huge variety of tools, collaborators, and scales in a complex system – from the biochemistry of the soil to the people who must work with it. This must keep your work interesting.

It is fascinating to work with a highly heterogeneous resource like soil, which harbors an incredible amount of biodiversity! The field has rapidly evolved over the last few decades, and now we can capture and understand processes that are critical for the cycling of elements at a very tiny scale. How cool is that? Furthermore, like soils, the science itself is very diverse – it brings together concepts from Chemistry, Biology, and Physics, scaling up processes happening within a soil aggregate to a given field and ultimately to the landscape level. My work has embraced such diversity, and I have been fortunate to collaborate with colleagues from different areas, learning how to bring together various concepts and ideas to understand how humans interact with the land.

Who are you working with right now?

My work has benefited from the local synergy between the University and the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). For example, my current work on soil organic carbon is being done in collaboration with Dr. Monika Gorzelak, a Microbial Ecologist. On top of analyzing soils for carbon chemistry, we are also looking at how microbial communities are shaped by land use and depth and the connection between soil organic matter composition and microbial metabolism in croplands. My previous research on biochar was accomplished by working with Dr. Tim McAllister, an Animal Scientist, and Dr. Xiying Hao, a Soil Scientist at the AAFC's Research Centre as well. This was an enriching experience that yielded several peer-reviewed publications and allowed me to present my result in several national and international meetings in North America and Europe.

Why uLethbridge?

The University of Lethbridge is strategically located in the heart of southern Alberta's agricultural hub. This positions our institution in a thriving place to coordinate research and serve as a bridge between science and applied knowledge. The Faculty of Science & Arts is extremely diverse, with world-class researchers leading cutting-edge research in many areas. My career as a young scientist has benefited from this multi-disciplinary environment; facilities like Science Commons are superb, with instrument accessibility that you don't find everywhere! I want to take this opportunity to thank Tony Montina and Mike Opyr (University of Lethbridge NMR Facility) for their continuous help and support in collecting solid-state NMR spectra.

Thank you for taking the time today, Carlos! Before we let you go - tell us one fun fact about you!

I grew up in a pretty flat area of central Argentina, where you can only find some hills nearby, but nothing like the Rockies! Having said that, I take every opportunity I have to visit Waterton National Park and sometimes the Banff area. I enjoy camping and hiking with my wife during summer.

If you'd like to keep up with Carlos and his research, you can either connect with him on LinkedIn, Twitter, or peurse his publications on ResearchGate.