Sara Citron, a PhD student in the University of Lethbridge's Department of Neuroscience, was selected as a Smithsonian Institution Ten-Week Graduate Student Fellow this summer. Starting in August, the fellowship offers her a ten-week internship at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., where she will study extinct birds of the genus Apteribis, flightless birds from the ibis family.

“This might be a little weird, but it’s not just birds that interest me; I really like everything that has vertebrae,” laughs Citron.

Citron’s journey into paleontology began in her country of origin, Italy, where she studied natural sciences at the University of Padova and later pursued a master's degree at the University of Pisa with a specialization in conservation and evolution, particularly focusing on paleontology.

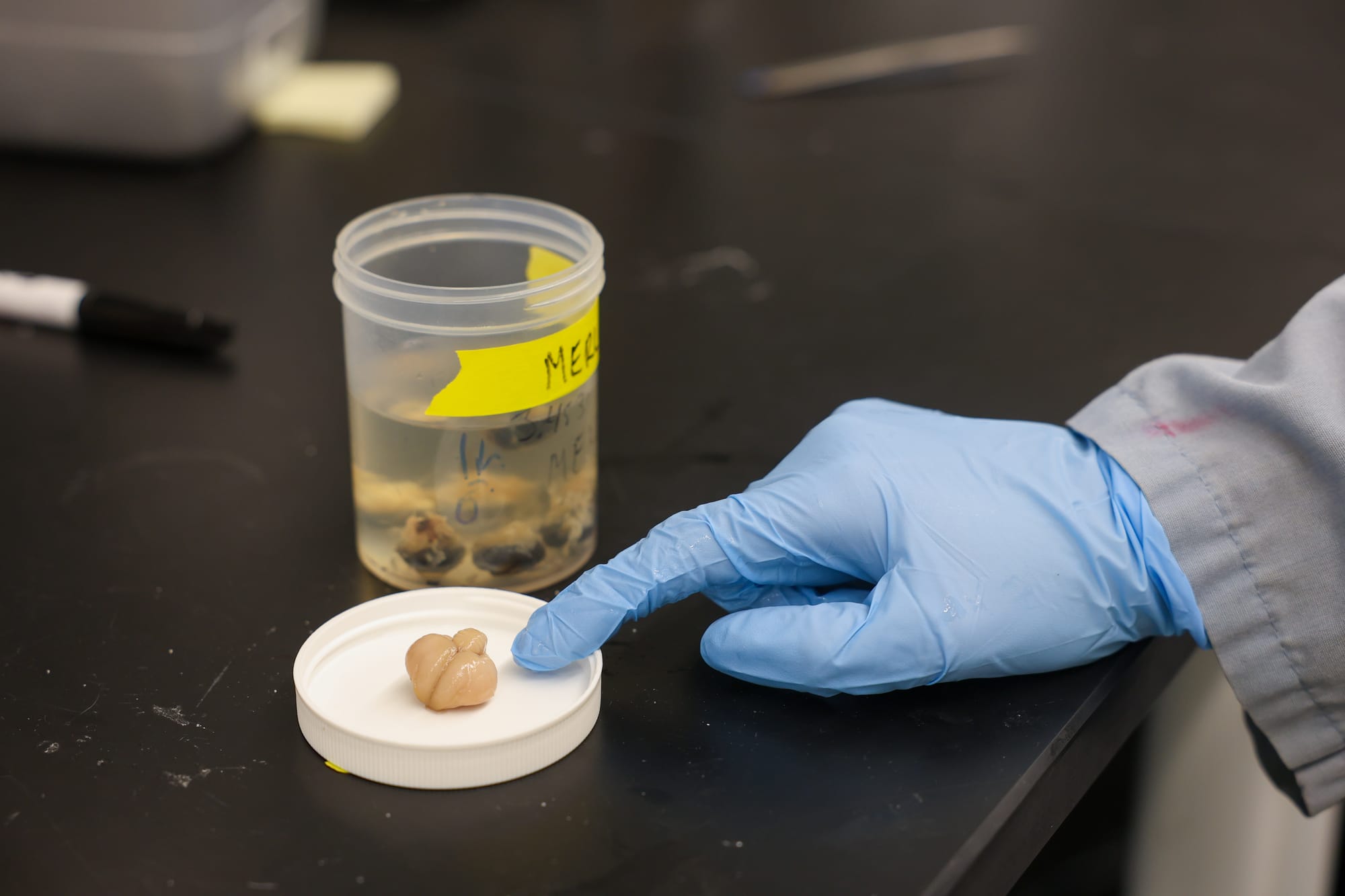

Following her studies in Italy and some delays due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Citron arrived at ULethbridge, eager to focus on birds under the mentorship of professor Dr. Andrew Iwaniuk. With access to cutting-edge technology in Iwaniuk’s neuroscience lab, she currently studies brains and sensory systems of birds using advanced CT scanning techniques. Her work aims to deepen understanding of avian evolution and contribute to the field of paleontology by studying ancient species.

“One of my main motivations for pursuing research and academia is the possibility of discovering something no one knew before,” she says. “For many years, people have been collecting fossils but not studying them. They put them in a box in the museum and forget about it. So, there are many specimens in boxes waiting for someone to take it out and study it.”

At the Smithsonian, Citron will have that opportunity. Over the course of ten weeks, her primary focus will be on the ornithological collections, collaborating closely with Dr. Helen James, a curator renowned for her expertise in bird anatomy and fossil birds. Together, they will use CT scanning of both living and extinct birds to reconstruct the brains and sensory organs, such as the eyes and specialized touch receptors in the bill tip of the Apteribis.

If her schedule permits while at the Smithsonian, Citron hopes to incorporate another passion of hers—painting and illustration—to visually represent the evidence she uncovers through a practice called paleoart.

Looking ahead, she envisions a future where her academic pursuits allow her to continue as a researcher and professor. However, her ambition extends beyond personal achievement; she hopes to inspire appreciation for the biodiversity of our planet and the critical importance of scientific inquiry in safeguarding it.

“I find that every single species on the planet has the potential to be helpful and interesting,” Citron states. “I really hope the world recognizes this is the only planet we know to have life and it’s worth knowing more about it.”

- meaningful research and work-integrated learning opportunities

- flexible, future-focused programs

- supportive campus communities

- generous student funding

Explore programs