As Dr. Bryan Kolb (DSc ’15) prepares to retire at the end of the year after an almost 47-year career, it’s only fitting to ask him to reflect on his time here — for maybe a half-hour — over coffee. An hour-and-a-half later, we’ve only skimmed the surface. It turns out Kolb’s quite a raconteur.

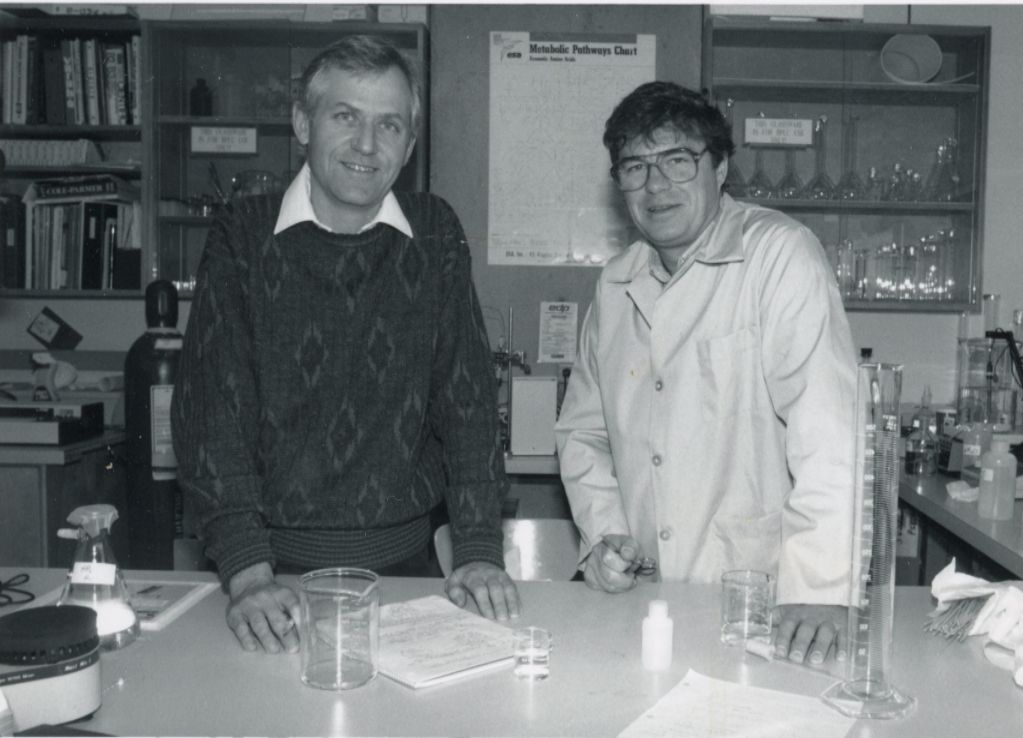

Born and raised in Calgary, Kolb is a world-renowned neuroscientist and a founding father, along with Dr. Ian Whishaw (DSc ’08), of the field of behavioural neuroscience. Over the course of his career, he’s been awarded four honorary degrees, elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada. He helped define and build the field of behavioural neuroscience from its earliest times as an offshoot of psychology.

“I think we were lucky to be in the right place at the right time,” says Kolb, referring to himself and longtime collaborator Whishaw. “Basically, it was a conspiracy of circumstance. We were in the field when it started. By being here, we could do whatever we wanted. Nobody bothered us. We weren’t really planning ahead; we were just doing it. When I look back on it, I have to pinch myself because people are making a fuss over my retirement. It sort of just happened. We didn’t really see it as that big a deal.”

As a youngster, Kolb enjoyed science class but his career dreams were fixed on a different field, one that was 110 yards long.

“I thought I would be a professional athlete,” he says. “My dad played for the Calgary Broncs, which became the Stampeders. So, it was football. Both of my grandfathers played pro baseball and I was expected to follow the line. I was good at most sports, but not outstanding at any of them. I thought that I could have made the Calgary Dinos football team. Their first year in existence, I was invited to the camp. Then I learned that the practices were four hours long. Well, that wasn’t going to happen because I was in a car pool. We lived in Britannia. There was no Crowchild. You had to go through downtown to take the bus. It took about an hour and a half and you had to transfer twice. So that was the end of that. I just said no, I’m not doing that. But I didn’t tell my dad for some time.”

Joining the rat pack

As a student at the then University of Alberta — Calgary (UAC), he was taking six courses a year, one of which was statistics, where he met Whishaw. He also took an introductory psychology course which consisted of three lectures and a tutorial every week. He enjoyed the tutorials and that caught the eye of the tutorial instructor Karen Ogston, who asked if he was interested in working with rats in a lab setting.

“I went ‘Oh, what’s a lab?’” Kolb says.

When you grow up in Alberta, rats are bad — very, very bad. Kolb was interested in the opportunity but he somehow had to overcome his bias toward rats first. Working in the concession at the Calgary Zoo at the time, he had the opportunity to wander around with the caretakers. He got to know the animals and came around to the idea that he could work with rats after all.

After completing his bachelor’s degree, he signed up for graduate studies and did an MSc at the University of Calgary and then a doctoral degree at Pennsylvania State University. At that time, the latter part of the 1960s, scientists were asking basic questions that would seem out of place today.

“In those days, people weren’t talking about brains; they were just looking at behaviours,” he says.

Kolb concluded he should be studying the brain, but the field of behavioural neuroscience didn’t exist at the time. The best he could do was study physiological psychology and one of the best places for that was Penn State (Pennsylvania State University). Kolb set out to discover if the rat brain had a prefrontal cortex.

“In 2022, people can’t believe that was a question, but in 1970 that was a question,” he says. “It was a tough sell at first.”

But Kolb believed he was on the right path and he stuck to his inner conviction. As he worked toward his PhD, Kolb’s supervisor was at Cambridge University (UK). When Kolb completed his thesis, which proved the rat brain was very similar to the primate brain and had a subdivided prefrontal cortex, his supervisor refused to sign off on it initially because he didn’t believe the results. He later came around and approved Kolb’s thesis.

Kolb and his wife — she worked at a department store while he earned $200 per month on an NSERC scholarship — didn’t have much money during those years.

“We couldn’t even afford a telephone,” he says. “I look back on it somewhat fondly. I was allowed to buy one case of beer a month.”

When he was ready to graduate, he learned he had to pay a graduation fee of $100.

“I said ‘A hundred dollars! Does the dean need new golf clubs?’ The dean came over from his office and said ‘That’s not funny.’”

He phoned his parents from a pay phone to ask if they would loan him the $100. They wired the money and refused to accept repayment when Kolb could afford it as a postdoctoral fellow at Western University.

The worst of times

“I was at Western for two years and I was unemployable because all fields have fads,” says Kolb. “So, if you were doing hormones, that was sellable. Another post-doc and I were applying for the same jobs and he got them all. I think I had 60 letters, which I politely called PFO letters. I just taped them up in the wall in my office. I had two from here.”

Thinking he had no future, he applied for jobs in Calgary, including the City of Calgary, figuring he could cut lawns in the summer after his post-doc was done. But the wife of his supervisor at Western was a neuropsychologist and she arranged for Kolb to go to McGill University to work with Brenda Milner (DSc ’86), who pioneered research into the human brain and is considered a founder of the field of clinical neuropsychology and cognitive neuroscience.

When he got to The Neuro, as the Montreal Neurological Institute was called, he wanted to learn about the human brain so he asked the graduate students what they read. They told him there was nothing to read. He checked out the library and found that was indeed the case. Since there were no courses he could take, Kolb decided the best option would be to offer a course and, in order to teach it, he would first have to learn it inside and out himself. He asked people at the hospital to recommend their must-read papers and, after reading them all, he designed a course he called human neuropsychology. The department chair scoffed at the idea of such a course, telling him there was no such field and no one would sign up to take it.

“I said ‘How many would you need?’ He said ‘Six or eight, something like that.’ I said ‘Can we try?’ He just laughed and said ‘Sure, we can try but it won’t fly.’ I gave him the course outline and I didn’t agree with him,” says Kolb.

In the meantime, Kolb kept applying for jobs at Canadian universities, including the University of Lethbridge, sending along the course he’d designed. As it turned out, five universities did offer jobs because of the course.

“They all said the only reason we’re interviewing you is because of this course; we want to see whether this is legit or not. I assured them that it was. So I gave my talks related to what would be in the course, as well as my PhD research and later research. I got the job here.”

He told the department chair at McGill to forget about the course because he was leaving.

“He said ‘You can’t leave; 175 students signed up for the course,’” Kolb says.

Kolb agreed to deliver some of the lectures at their cost while he began his new job at ULethbridge. It was 1976.

The dynamic duo forms

“Then I realized there was no book. So I thought, well, if I’m going to teach this course, I need a book. So why don’t I write the book?” he says.

The typical route of getting a textbook to print is to get a publisher first and write the book after negotiating on the contents. But Kolb dived right in and soon realized how much work it was going to be.

“So, I’d known Ian (Whishaw) since I was 18 — we sat together in statistics class in Calgary — and I said ‘Why don’t you help me?’” he says. “He said ‘I don’t know anything about neuropsychology.’”

Kolb suggested he take his course and Whishaw took him up on the offer when Kolb taught it for the second time.

“The students got quite a different course because, of course, we argued the whole time. If you know Ian, that just makes sense,” Kolb says.

Whishaw’s challenges led to lots of discussion and ultimately, he agreed to help Kolb write the book. After they compiled a draft, they wanted to make sure it was usable, so they copied it and gave it to students for feedback, with full freedom to write in the margins.

They rewrote the book over the summer and sent a chapter to all the major publishers in North America except one because they didn’t publish in that subject area.

“Every single publisher wrote back to us with the same thing — there’s no such field. Therefore, there’s no such course. Therefore, there’s no such book,” Kolb says. “Ian was furious with me, saying ‘You ruined my life.’ He said ‘We should send it to Freeman because it’s the only one we haven’t written to.”

Kolb sent it to W.H. Freeman & Company where the acquisitions editor was a man known as Buck Rogers.

“He phoned and said ‘This is Buck Rogers from Freeman. Don’t sign with anybody else; we’ll do your book.’ I remember saying ‘Well, we’ve had quite a few offers.’ And he laughed and said ‘No, you haven’t,’ Kolb chuckles.

Rogers happened to have Richard Thompson, a neuroscientist who had a best-selling book on the brain and behaviour, as a neighbour. Rogers recruited Thompson to read the chapter and he advised Rogers to publish the book, telling him it was a new field and that the book would define it. That was 1980.

Turns out Thompson was prescient. The book, Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, is now in its eighth edition and is geared toward upper level undergraduate and graduate students. They’ve since co-authored another book, An Introduction to Brain and Behaviour, geared toward second-year students. That book is now in its seventh edition.

Getting going

“In the 70s and 80s, this was a totally different university,” Kolb says. “When I came here in 1976, I think we had 900 students and there was talk of closing the University.”

In about 2008, Kolb happened to be seated next to former-premier Peter Lougheed at a dinner. To Kolb’s surprise, Lougheed knew who he was. Kolb figured he recognized the name because his father had grown up with the Lougheed family as neighbours. But Lougheed, when he was in power, had been informed that two guys — Kolb and Whishaw — were changing the University and so he had decided they would take a chance and give them the opportunity to make a difference. Lougheed noted that “It worked, didn’t it?”

University Hall was the main building on campus and, because of their research activities, Kolb and Whishaw soon found themselves needing more space.

“We had to fight to get space. We had to fight for everything,” Kolb says, adding one colleague even described them as a cancer on the University because they were doing well and expanding, even though they were looking at a space that wasn’t being used.

“We have animal care staff now and a veterinarian,” Kolb says. “Then the animal care staff were Ian and Bryan. Between classes we would clean the animal cages and do the feeding and watering. And we taught between five and six courses. At one point, I had three grants and in our department of psychology, besides Ian and me, there was one grant. There were two grants in biology and two in chemistry and none in physics. This just wasn’t a research university in any way. So I think that we can take some credit for changing the place by being a cancer.”

It was the best of times

The Canadian Centre for Behavioural Neuroscience (CCBN) opened in 2001 under then president Dr. Bill Cade (LLD ’12). The previous president, Dr. Howard Tennant (LLD ’05), had championed the idea of a new building utilizing funds from the newly formed Canada Foundation for Innovation. All they’d need was an industrial partner.

The need for more space was reaching a critical stage. Kolb had applied for a Killam Research Fellowship, a prestigious award that supports scholars of exceptional ability with two years of salary to allow them to focus on their research. Tennant said he’d add another year to the fellowship and hire a replacement if Kolb succeeded. Kolb secured the fellowship and his replacement was hired, but the lack of space meant the new hire had a closet for his lab.

As for the needed industrial partner, Neuro-Detective, a company started by Kolb and Whishaw, fit the bill but they couldn’t get quite enough funding together. Tennant approached the Heritage Foundation and eventually secured enough money.

“It was like the Field of Dreams. You build it and people come,” he says. “And we kept expanding and expanding. A lot of it was shelled space and within a couple of years, that was all taken up. And then we got another CFI to expand it and put in the MRIs. And then we got another CFI when Dr. Bruce McNaughton was hired with the Polaris award.”

While an undergraduate degree in neuroscience had been available for a while, a master’s degree was added and finally a PhD program, with the first doctoral graduates crossing the stage in 2004.

“It’s one of the best groups in the country,” Kolb says of the CCBN. “If you look at the statistics and you correct for number of faculty, it’s the best in the country. You can’t compare us to UBC where they’ve got 100 faculty or to U of A, but if you simply correct for faculty size and do all your statistics, such as number of publications and citations, we come out first.”

What’s next?

“People ask if I will miss it,” says Kolb. “I’ll miss being in the know. But I’m past my best-before date. So is Ian. We know that. I can’t work after dinner anymore. I’m just tired. I don’t miss working 24/7. I don’t miss cleaning rat cages. I don’t miss teaching six courses.”

Beyond his official retirement date of Dec. 31, Kolb says he has some 20 to 25 papers to write and expects that’ll take about three years. He’ll be on campus from time to time and expects to continue being involved with the Martin Family Initiative and its programs for Indigenous youth and children. And he hopes the CCBN continues to thrive in the years ahead.

One last question

When asked to recall a favourite memory from the last 47 years, Kolb goes back to a time when he got a surprise phone call.

“One of the favourite memories is the phone ringing and me picking up the phone and this person says ‘I’m looking for Bryan Kolb.’,” he says. “I said ‘You’ve got him, but please be quick because I’m really busy.’ And he said ‘I’m calling from the Governor General’s office.’ I said ‘What?’ Maybe I’m not that busy. That was the Order of Canada. He said ‘You’ve been selected to be an Officer of the Order of Canada; will you accept? And I said ‘Let me think it over. Yes, I think so.’”