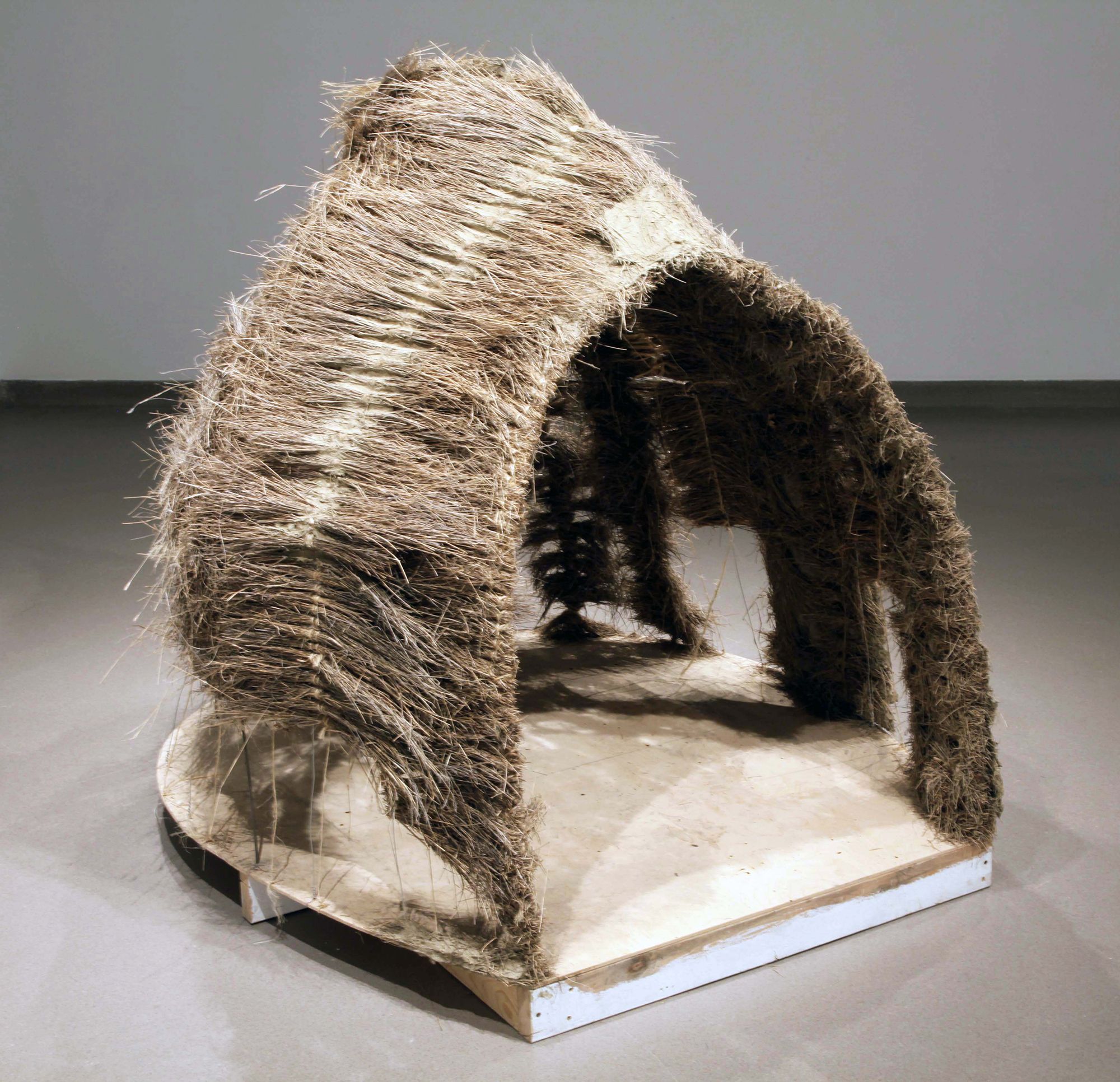

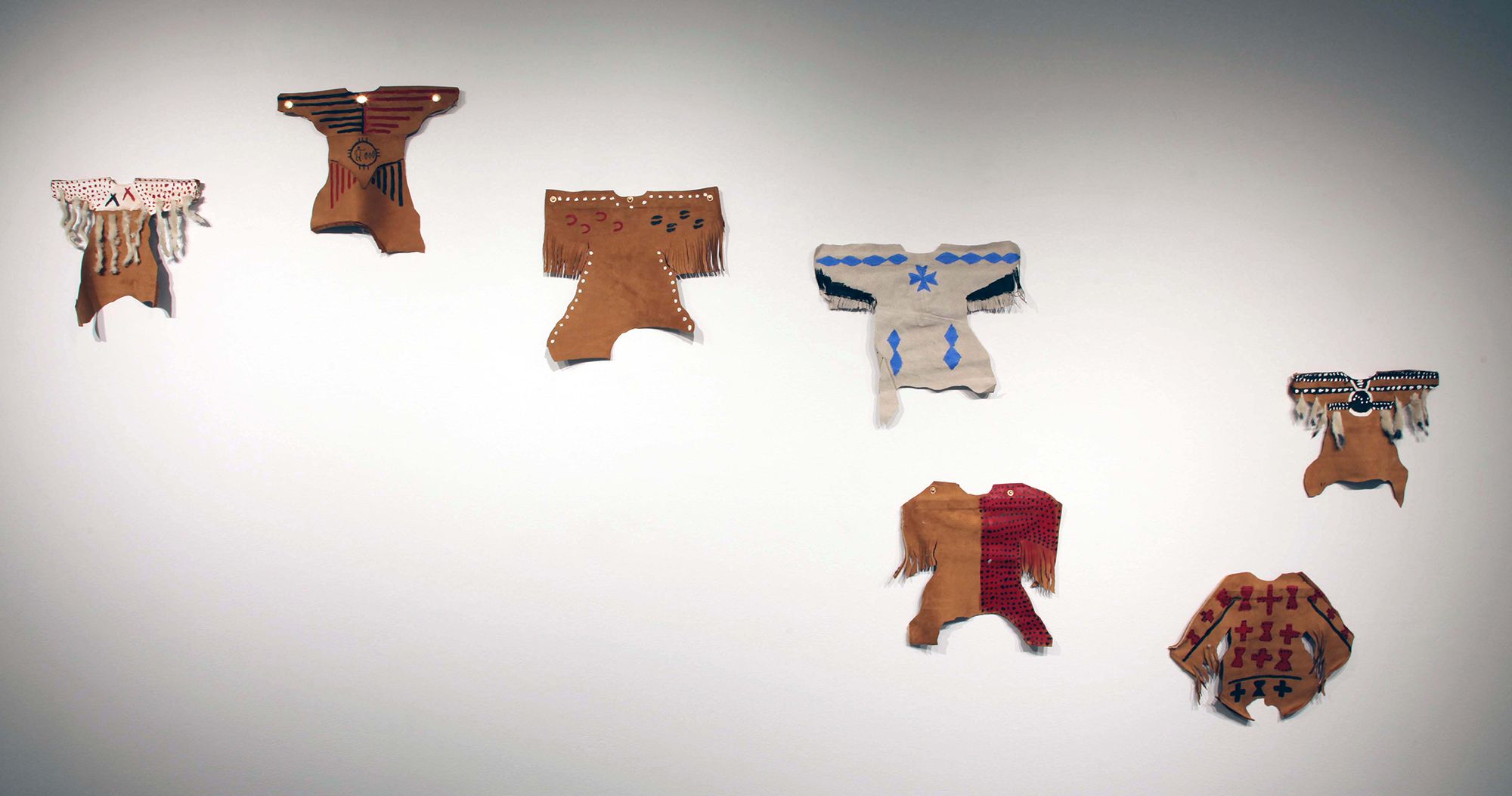

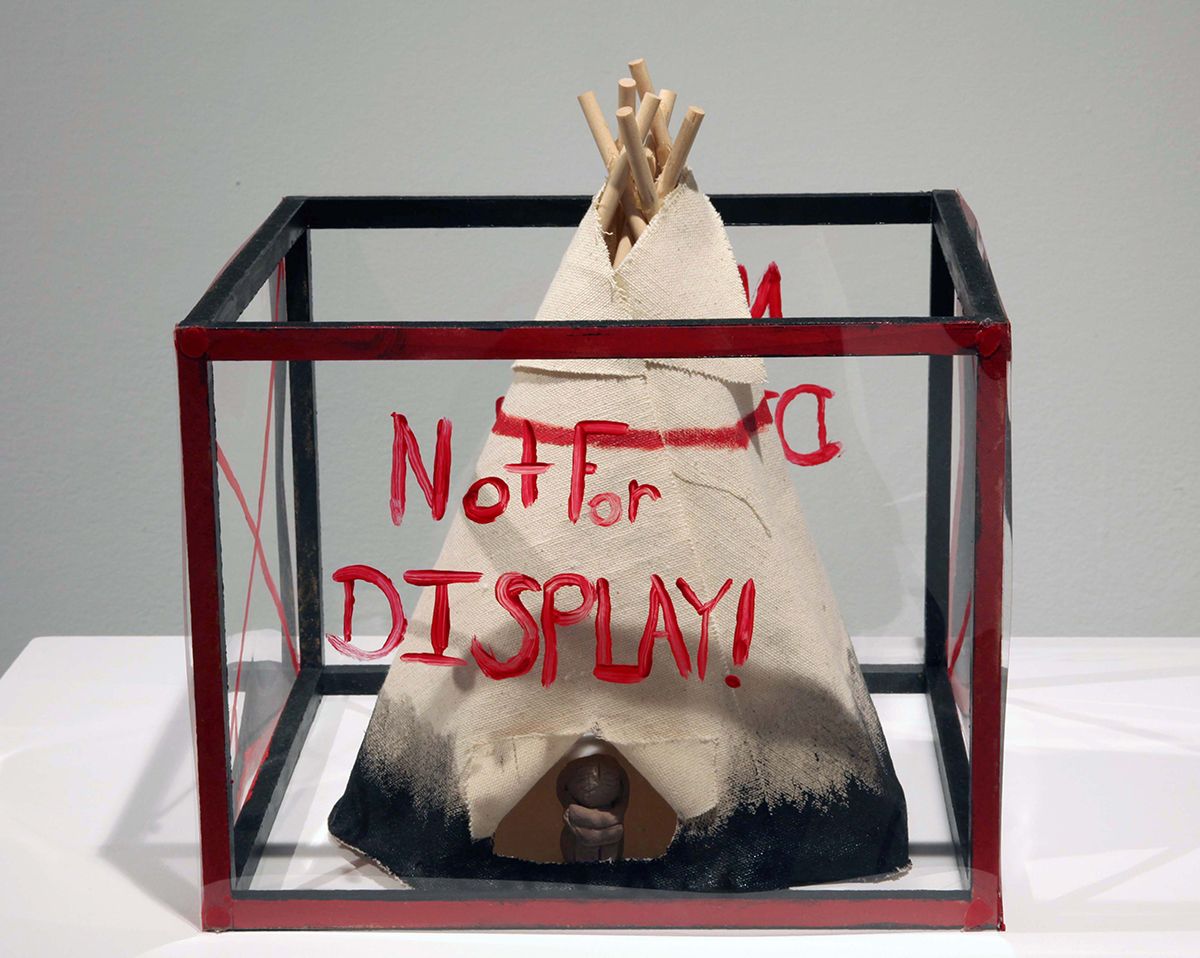

Like many things cancelled in 2020, the University of Lethbridge’s Hess Gallery was preparing to open an exhibition of student work as the global pandemic was declared in March 2020. Students enrolled in Dr. Jackson TwoBears Indigenous art studio class were dropping off works and finishing up their projects when the University had to close, leaving the gallery with some finished works, some works ready for installation, and some artworks not yet delivered.

“As we all adjusted to closures of public spaces and working from home, the issue of how to finish this exhibition hung over us,” says gallery director and curator Dr. Josephine Mills. “The students had done a fabulous job, working hard and engaging with processes, concepts, and imagery of objects involved with Mootookakio’ssin – a major research project to create detailed digital images of historic Blackfoot objects housed in three museums in Britain. We had promised the students an exhibition and they had put in extra effort to make work that could stand up in a public display.”

The students are the first to tackle the daunting task of working with the Mootookakio’ssin project. Their exhibition was to provide an initial stepping-stone for students from or living in Blackfoot traditional territory to connect with students working with research partners in Britain.

To begin Mootookakio’ssin, the Canadian component of the team, made up of Elders from all four tribes in the Blackfoot Confederacy, uLethbridge researchers, and artists, travelled to Britain in July 2019 to meet up with the British team members. Together they visited the British Museum, the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology at Cambridge University, and the Horniman Museum, London to view Blackfoot objects that had come from Blackfoot territory (Southern Alberta, Canada and Montana, USA) and now are held in these collections in the UK.

“The Elders selected the objects we looked at, told stories prompted by the objects, and the team made digital images of the objects,” said Mills. “Words fail to describe how deeply moving and emotional these visits were.”

For the Blackfoot, there is no equivalent to the term ‘object’ because all things are living beings – the ‘objects’ have a life force and the Elders were waking these objects after a century or more of separation from their people.

“It’s hard for non-Indigenous people to conceptualize this crucial idea of the connection between the objects and the people, of the life force that they each generate in the other,” shares Mills. “I could see how lifeless and incomplete the objects were without the people to wear them, use them, and have them play their role in telling stories and sharing knowledge.”

Mills didn’t see the connection with the uLethbridge Indigenous Art Studio student’s work until she returned to see them on campus in October, 2020.

“When restrictions began to open up, I went with David Smith, Assistant Curator and Preparator, to remind ourselves what student work we had as we began to think about an online version of the exhibition. Standing in that small storage room, I felt so sad looking at objects that lacked the vibrancy of the artists, the energy surrounding the exhibition; works that were incomplete, that didn’t have their context. And then it struck me, this is like visiting the historical objects in the museum storage in England.”

Historical objects convey information, and in the case of Indigenous objects in British museums, they provide the means to explain the on-going legacies of colonialism and have the power to dismantle colonial narratives and rebuild relationships between people. Talking about the objects opens doors and creates paths to understanding.

“Here in Lethbridge, standing in the small storage space looking at the forlorn student art works that had been left behind when the quarantine began, I learned one of the many important lessons I am gaining from working on Mootookaikio’ssin,” says Mills. “I realized that non-Indigenous viewpoints also include a vital connection between people and art works, even if we don’t conceive of the objects as living beings.”

Stories for British Museums, the inaugural uLethbridge student exhibition connected to the project, has provided a crucial first step in building connections between the historical Blackfoot objects and current artists and audiences. The version presented on the uLethbridge Art Gallery’s website is not the same as the exhibition that never came to be, yet it is a valuable link in the research process and demonstrates the strength of the artwork produced by the student artists.