Reading is at the root of learning, and the teaching of reading has been a key interest of a pair of University of Lethbridge teacher educators for a long time, albeit in different ways.

Over the last year, the Faculty of Education’s Dr. Robin Bright (BA ’79, BEd ’82, MEd ’88) and Dr. Chris Mattatall have combined forces on work that aims to empower and inspire educators in their teaching of reading, while gaining a greater understanding of what’s happening in the brain while children are learning to read.

“We had always wanted to research together because we have different angles towards the same goal,” says Mattatall. “My background is more the cognitive underpinnings of how the brain learns to acquire reading, and Robin’s is showing the instructional methods that are most likely to raise students’ reading achievement.”

Bright says once they started considering what joint research could look like, it was clear that this was the perfect time to bring their backgrounds together.

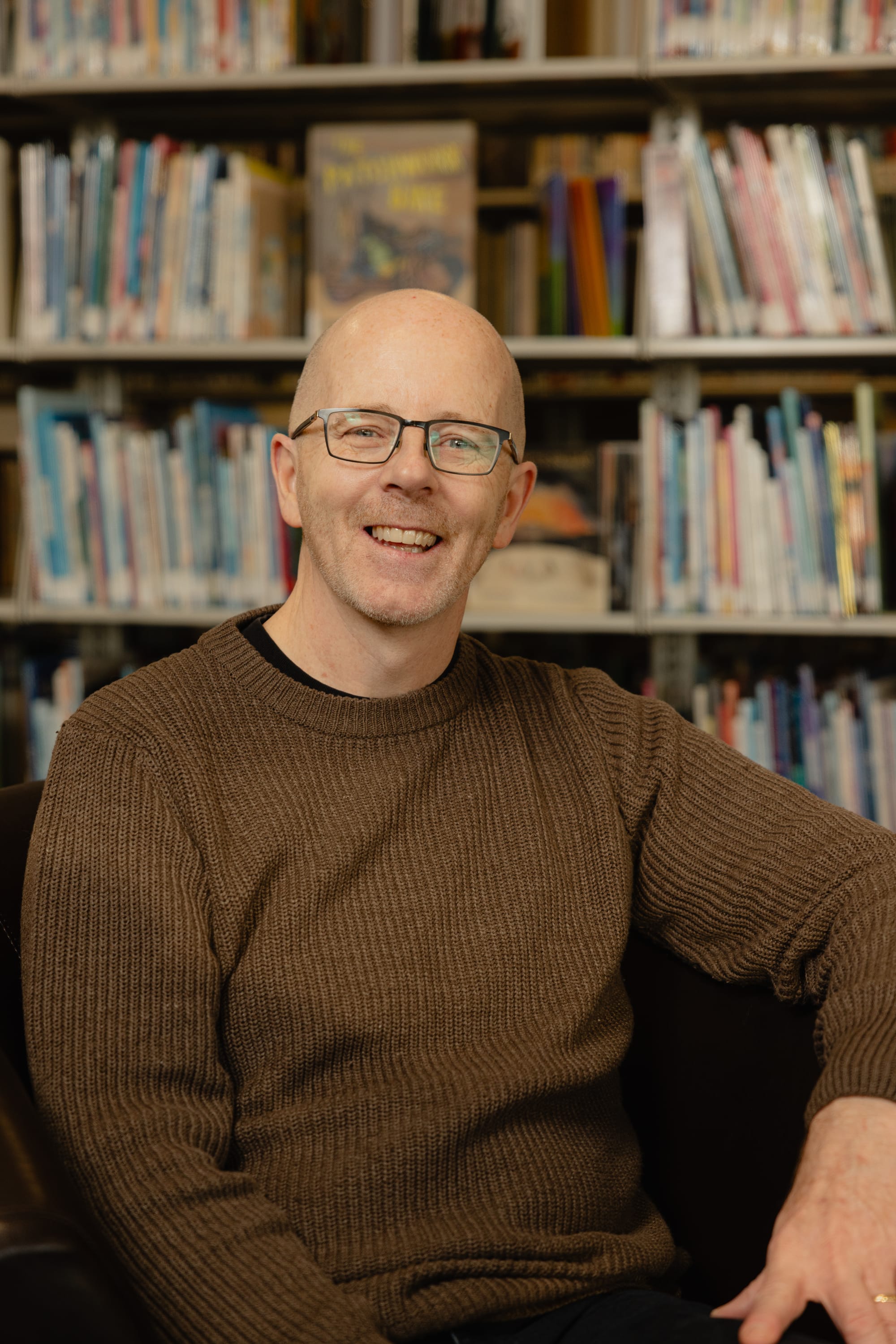

Dr. Robin Bright (left) and Dr. Chris Mattatall (right) have been working together on a project that combines professional development for teachers and research.

“Right now, that’s what teachers are asking about; they want to know how reading takes place, but they also want to know how to teach reading, and those things aren’t exactly the same,” she says. “There’s been curriculum changes, changes in pedagogy and everybody is thinking about teaching reading right now.”

The pair connected with Dr. Adam Browning, Learning Director for southern Alberta’s Palliser School Division, who was looking for professional development opportunities for teachers. In planning for that professional development, Bright and Mattatall saw the opportunity to engage in unique work that would align professional learning with research. According to Bright and Mattatall, Dr. Browning also brings his research expertise in Early Childhood Education to the work.

Their study has been laid out in three phases. First, surveying the teachers they’re working with to better understand their current mindsets around teaching reading, followed by professional development with those teachers throughout the school year and finally a follow-up with those same teachers at the end of the school year.

Mattatall says a common phrase in cognition, “what you know determines what you see,” has been a guiding idea during the work.

“The knowledge they have determines how they interpret the situation, how they see their students’ abilities or inabilities, and then what they do next,” he says. “We intentionally put out the survey first, to find out what they know and understand to start. After we go through these workshops, we think the end result is going to be achievement gains in students, and we’re really excited that we’re working through the teachers to do that.”

The work is especially timely as classrooms have become far more complex than they were even 10 years ago, something the pair witness firsthand as professors in the Faculty of Education.

“We’re lucky that we are supervising practicum students in schools, because we see the reality of what teachers do every single day,” Bright says. “A lot of researchers don’t have that experience in schools, so I think that’s a real distinguishing feature of our work.”

Mattatall believes many of the challenges teachers face are a result of society pressing in on the mental capacity of children.

“This generation has never known a time when they’ve not been connected to social media and commercials that are 10 seconds or eight seconds long,” he says. “They are bombarded every day with high energy things that take their attention, and then a teacher wants you to slow down and focus on the sounds of letters? It can seem impossible.”

Introducing new strategies to get through to students, all while making that learning fun for both the teachers and the learners, has been a primary focus of the work.

“Teachers are hungry for new things to try, but they also want to know what is happening in the brain when students are learning to read,” Bright says. “That’s what Chris brings in; he’s been able to talk about things like the reticular activating system, which I had never heard of before, but it made so much sense to me that that’s why some students really struggle.”

The reticular activating system (RAS) is a tiny cluster of neurons in the brainstem that all incoming information from our senses must pass through before going to the thinking part of the brain. The RAS acts as a filter to protect the individual from the threat of harm, including engaging in things that might be embarrassing or make us look less intelligent. Bright and Mattatall recognize that many academic activities require a degree of risk, error and feeling vulnerable. Unless children feel they can take those risks, some learning will not occur.

Mattatall says suggesting strategies for getting around the challenges presented by the RAS has been where Bright’s expertise in creative ways to teach reading has really combined well with his own.

“The RAS acts as a block. Kids don’t want to struggle and look stupid, so they avoid that by not doing the work,” he says. “One way to get things through the RAS is with games, fun activities, things like singing, and then for a whole bunch of kids you’re camouflaging learning through fun.”

Through their work so far, the pair agree that the most rewarding part has been seeing what incredible jobs teachers are already doing, despite the challenges they face, and reassuring those educators that they’re capable of getting students where they need to be.

“Really amazing, conscientious teachers question themselves on a regular basis, which is a really great attribute to have, but it shouldn’t cause you to lose your confidence,” Bright says. “So part of what we’re trying to do is help teachers recognize that they’re doing a great job, and any new knowledge can be incorporated into their practice without that meaning that what they were doing before was wrong.”

Mattatall agrees that ultimately, teachers just want to do well by their students.

“Teachers love their jobs, they love their students, and it kills them if they can’t see progress the way they want,” he says. “What we’re saying is, ‘okay, forget all the noise that’s out there, your knowledge will determine what tools you should use and feel good about using to accomplish your task.’ We’re trying to right the ship and calm things down, because I think teachers are doing a really, really good job.”

- Paid work terms

- Hands-on career & research experience

- International study

- Awards, scholarships and a range of student support

Learn how!